Artist James Turrell Creates Intense Sensory Experiences

Looking at Light

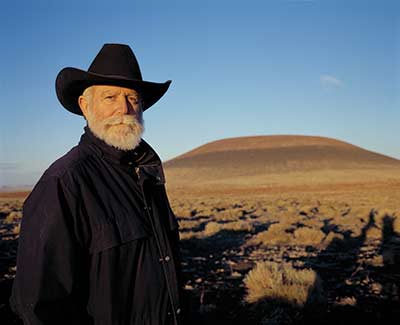

Currently on display at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, James Turrell: A Retrospective showcases nearly five decades of the creative and intellectual life of artist James Turrell (MFA, 1973) .

We seldom think of the artistic process in the same way we might think of traditional scholarly research. Those wholly unacquainted with the process might envision artistic frenzy overtaking the individual, who is then spurred into creative action. And even those who know or are themselves artists may find the process ineffable. But much like the traditional academic—who begins with a question, evolves a hypothesis, conducts research, and, finally, makes a discovery—there is in James Turrell’s body of work the sense of that same process: the bud of a youthful idea blossoming over decades, each phase of his career guided by a common question.

While a student of psychology at Pomona College, and later as an MFA recipient at CGU, Turrell became involved in the burgeoning Los Angeles-based light and space art movement. As the name suggests, these artists use light and space as their media with the aim of creating intense sensory experiences, evoking psychological and metaphysical awareness. It is within this context that Turrell began to wonder about our relationship to light; and as you peruse the exhibition at LACMA, Turrell’s guiding question is illuminated: We usually look at something that light reveals; but what does it mean to look at light itself?

The exhibition at LACMA is expansive, with older works in the Broad Gallery and newer pieces in the Resnick Pavilion. The museum had to construct individual viewing rooms to house each piece or collection of pieces (a process that took five years of planning and three months of construction). Guards guide the flow and help visitors approach the pieces properly, and several pieces are accompanied by quotes and explanations by Turrell. This meticulous orchestration of movement and information lends the whole exhibition an air of performance, one in which you, too, are an active participant.

The Broad Gallery exhibition begins with prints and plans from Turrell’s earlier works, including his first light projections and plans from The Mendota Stoppages portfolio (1969-74). Turrell started to receive recognition as an artist with The Mendota Stoppages, a series begun in 1966 at the former Mendota Hotel in Santa Monica. By blocking all external light from reaching the interior space and then allowing some light back into the studio by cutting into the building, The Mendota Stoppages was an elaborate light performance that featured both natural and artificial light sources. “The big thing,” Turrell told art historian Craig Adcock in a 1986 interview, “was that the interior space was created by the light and not by the physical confines of the room.”

Moving through the exhibition you then come into a large, unlighted room with what appears to be an illuminated cube in the opposite corner. Inexorably drawn to it, you find it is not an object at all but a projection of light that, by virtue of its shape, angle, and position in the room, is seemingly three-dimensional and tangible. The piece, Afrum (White) (1966) is not only the chronological successor to The Mendota Stoppages, but the intellectual one: In Mendota, he shows how light can define space; in Afrum (White), it is the light itself regardless of space that becomes the art.

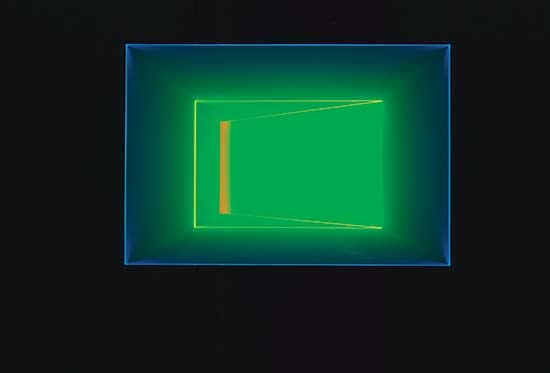

A variation on the theme of Mendota, Key Lime (1994) pushes the idea of light defying physical space to its logical extreme. Towards the end of the exhibition, you enter a large, nearly lightless room where planes and beams of different-colored lights intersect at angles such that the depth of the physical space is inscrutable. The uncertainty as to whether the room extends back 30 feet, as is visually suggested, or whether the geometry of light on a wall simply creates that illusion (museum guards prevent visitors from approaching the “event horizon”) exemplifies the confounding effects of light and space at play: We use our senses to guide us through the world, but what happens when they betray us? What happens when the senses no longer guide, but mystify? What, then, of reality?

As with the “observer effect” in quantum mechanics, wherein a particle’s behavior varies depending on the viewer, so, too, do Turrell’s pieces rely upon the subjective position of their audience. As Turrell describes it in a video produced for and played in the exhibition, “You’re not receiving perceptions, but creating them . . . You’re not only looking at a painting or a work of art, but looking at yourself perceiving.”

Nowhere is this more acute than with the hologram pieces, which are situated at the midpoint of the Broad Gallery. The series of mounted holograms are created not by light projection, as with many of the other pieces, but recorded light waves on handmade transparent coating applied to glass. As you move about the pieces, light emanates from nearly every angle, giving the appearance of depth from almost any perspective, shifting in both shape and proportion. What the viewer sees depends on the viewer.

And this is the crux of Turrell’s decades-long thesis: by making the art a participatory experience, the traditional delineation between art and viewer is eradicated, as the viewer’s viewing is what brings the art to life.

While the exhibition at LACMA showcases many of Turrell’s most famous pieces, major architectural installations are necessarily omitted (although videos at the exhibition show skyspaces, one of which, Dividing the Light, is a permanent installation at Pomona College). But no discussion of Turrell is complete without mention of his masterwork, The Roden Crater Project (1979-).

Based at Roden Crater, a 400,000-year-old extinct volcano 40 miles northeast of Flagstaff, Arizona, the art unfolds continuously, with the natural world the object of observation. Though it has undergone several permutations in its 30 years, as it currently stands, the interior of the crater consists of underground chambers and tunnels with viewing galleries into which light from the sun, moon, and stars pour variously and dynamically throughout the day and night.

Turrell says in his 1985 book Occluded Front:

Roden Crater has knowledge in it and it does something with that knowledge. Environmental events occur; a space lights up. Something happens in there, for a moment, or for a time. It is an eye, something that is itself perceiving. It is a piece that does not end. It is changed by the action of the sun, the moon, the cloud cover, by the day and the season that you’re there, it has visions, qualities, and a universe of possibilities.

Perception, change, engagement, light, and space—the hallmarks of Turrell’s works—are all present at Roden Crater. Part natural monument, part artistic laboratory, there, hypothesizing, experimentation, and creation all occur. Only with Turrell, the proverbial test tube is you, and the material with which he experiments is the fabric of the universe itself.

James Turrell at the Guggenheim (July 2013).