Passings: Joseph Maciariello (1941-2020), Peter Drucker’s ‘Legitimate Successor’

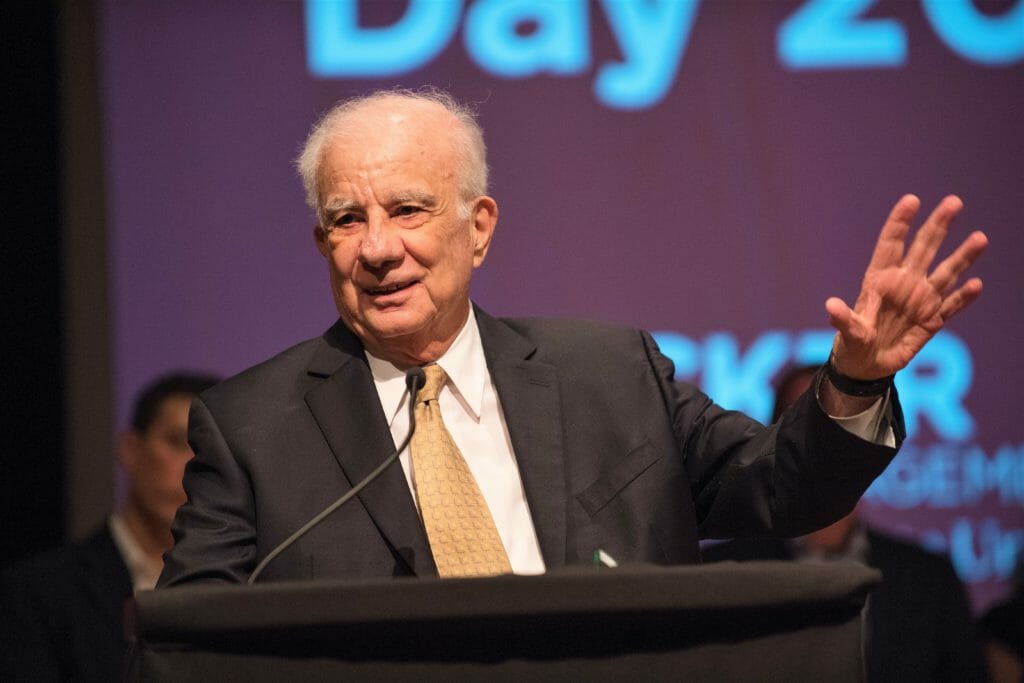

AS SHE STOOD AT THE PODIUM on Drucker Day 2017 and introduced Joseph Maciariello as the recipient of the Drucker Lifetime Achievement Award, Jean Lipman Blumen wanted the audience to clearly understand the role he’d played to Peter Drucker for many years.

To do that, she used an example not from the world of management, but from English literature.

Maciariello’s work reminded her of James Boswell’s tireless service to Samuel Johnson. The result was Boswell’s Life of Johnson, which many consider one of the greatest examples of literary biography.

“That is the model we see replicated in Joe’s selfless devotion to Peter Drucker and Peter’s astounding life’s work,” Lipman Blumen said.

An accomplished scholar and inspiring teacher whom many regard as Drucker’s legitimate successor, Maciariello passed away July 1 at his home in Claremont. He was 78.

For more than 40 years, Maciariello belonged to the university community, serving first in a joint appointment as Horton Professor of Economics at what was then Claremont Graduate School and Claremont McKenna College. More recently he had served as the Drucker Institute’s academic and research director as well as the Marie Rankin Clarke Professor of Social Science and Management Emeritus and a Senior Fellow at the Drucker School.

Maciariello stewarded the Peter Drucker legacy in the years after Drucker’s death.

The Drucker community mourns the passing of someone who was not only a careful steward of the Drucker legacy but also a kind, warm, and thoughtful colleague, mentor, and friend.

“Joe really embodied the idea of approaching management as a liberal art,” said Professor Katharina Pick, interim dean of the Drucker School of Management. She sent a message about Maciariello’s passing to the Drucker community last week. “Over the years, I got to know Joe as a funny, kind, gentle human being, a generous and supportive colleague, and a true Drucker scholar. This is a huge loss for our community and I will miss him.”

Maciariello’s passing drew similar responses from Drucker alumni and friends on the Drucker School’s social media account, especially Facebook.

“One of the best, most challenging professors I had at Drucker,” wrote Brad Bargmeyer (MBA ’99; MA, Politics, ’00). MBA grad Mark Luna added that Maciariello was “the Drucker School of Management’s final link to Peter Drucker. I was one of the fortunate ones to take his first class, Drucker on Management, which was a full 14 weeks. I still refer to the course assignments.”

(Read more comments about Maciariello here)

Early Years & Early Drucker Connections

BORN IN 1941 IN TROY, NEW YORK, Maciariello was the son of Italian immigrants and grew up in the upstate mill town of Mechanicville. He attended Rhode Island’s Bryant College, where he graduated summa cum laude with a degree in business administration, and Union College in Schenectady, New York, where he received a master’s degree in industrial administration and served as a member of the faculty.

Maciariello told interviewers that his Schenectady years were happy ones. He met his wife Judy in 1969 and they married in 1970 and soon started their family.

It was also during this time that he first discovered Drucker’s writings while working as a financial analyst and controller for Hamilton Standard, which was involved in the Apollo space program.

The space program project was complex, and it created many challenges for managerial culture. Maciariello couldn’t find a company manual to help him address these issues, so he searched his local libraries in Connecticut for an answer. That’s when he came across Drucker’s The Practice of Management.

Later, when he and Drucker were colleagues, Maciariello told him about his discovery and how he’d applied that book to the problems he was experiencing at Hamilton Standard.

“Peter said to me, ‘you had no alternative,’ and it wasn’t an ego statement,” Maciariello recalled. “He was right. There were no alternative books out there. He wasn’t bragging — he was stating a fact.”

Thanks to the support of his colleagues at Union College, Maciariello was able to enroll as a doctoral student in economics at New York University.

Maciariello first encountered Drucker himself at NYU; Drucker was teaching there, and it was the first time he had a chance to experience Drucker’s idiosyncratic lecture style—spinning wider and wider circles of history and philosophy around a specific management question before zeroing in on an answer.

Maciariello earned his doctorate at NYU in 1973, and his dissertation advisor was economist William Baumol, who was twice considered for the Nobel Prize in Economics.

Moving to Claremont

WHEN FRIENDS ALERTED HIM about a job opening at what was then called the Claremont Graduate School, Maciariello applied for the position. In 1979, he and his family moved to Claremont, where he accepted a joint professorship at Claremont McKenna College and CGS.

As an East Coaster, Maciariello said he didn’t know much about Claremont or Southern California. In fact, he said, all he knew was “that Drucker was there, and that was my primary attraction.”

For 26 years, Maciariello and Drucker were close colleagues. He told an interviewer that he recognized Drucker as that rarity, a true Renaissance person, and that he made every effort to connect with his senior colleague whenever possible.

“If he needed a ride somewhere, I gave him a ride,” he said. “And I always had many questions for him.”

In 1999, they started working closely together on a number of projects and kept going until Drucker’s death in 2005.

“He was ill at the time,” Maciariello said, “but I had the legs and he had the brains. So we made it work.”

The ‘Legitimate Successor’

REFERRING TO LIPMAN BLUMEN’S COMPARISON, James Boswell had been a gifted thinker and writer in his own right, and the same was true of Maciariello.

Three years after Drucker’s death, he published a revised version of Drucker’s 1973 classic Management—to which he added his deep knowledge of systems–to meet the needs of executives in the 21st century.

He would go on to amplify and expand on Drucker’s legacy in a number of other books as well, including Drucker’s Lost Art of Management: Peter Drucker’s Timeless Vision for Building Effective Organizations, The Daily Drucker, and A Year With Drucker: 52 Weeks of Coaching for Leadership Effectiveness.

“Joe was the ultimate scholar and gentleman. More than anyone, he promulgated the philosophy of Peter Drucker across the globe, in many industries, and in many different forms of organizations,” said Bernie Jaworski, who is the Drucker chair in Management and the Liberal Arts. “He will be sorely missed by his colleagues – and by the many other people whose lives he has touched.”

Maciariello also lectured widely on a vision he shared with Drucker: the need for corporate leadership to be more socially aware and to feel a greater obligation to uplifting and helping society. He lamented the absence of such leadership in the 2008-09 financial meltdown during a TEDx talk that he gave in Orange County. Watch here.

In recent years, he had worked with the Shao Foundation as well as the California Institute of Advanced Management, which established the Joseph A. Maciariello Institute of Management as a Liberal Art.

Along with the Drucker School’s lifetime achievement award in 2017, he also received an honorary doctorate from HHL Leipzig, Germany’s oldest business school (founded in 1898), in 2017.

During the Leipzig ceremony, Richard Straub, president of the Peter Drucker Society Europe, introduced Maciariello, stating that “nobody else in the world is better positioned for the mandate of advancing Drucker’s monumental legacy by building on the foundations he left and refashioning them to fit the future.”

In an interview with HHL Leipzig Professor Timo Meynhardt, Meynhardt described him “as the legitimate successor, not only to advance Peter Drucker’s legacy but also having contributed in a number of ways to advance his work.”

Meynhardt also asked Maciariello what he thought his own legacy would be, and he said he hoped to be remembered as a person of integrity.

“Your purpose continues to change as you change, and the closer we get to our senior time in a profession or in life, the more serious that question becomes,” he said. “It certainly was for Drucker. That’s the way he taught it, and that’s the way he lived it and I saw the power of it. And so I’m very committed to it.”

A Personal Tribute

FOR MANY IN THE DRUCKER COMMUNITY, Maciariello will be remembered not only for his scholarly custodianship of the Drucker legacy but also for his humanity.

One of those is Jeremy Hunter, who is the founding director of the Executive Mind Leadership Institute. Maciariello helped and advised Hunter in his early work on self-management. One day, Hunter recalled, Maciariello asked him, “What do you think is the most important quality a human being should cultivate?”

Hunter’s response was: “unconditional love.”

“Instantly, he beamed,” Hunter said. “I think it was at that moment that we became friends.”

Hunter’s friendship with Maciariello would deepen when Hunter was later in need of a kidney transplant. Unknown to him was the fact that Maciariello was the UCLA record holder for the longest-living kidney transplant.

“His intimate counsel about his experience illuminated an otherwise dark path for me,” he said. “Words are not enough to express the gifts that I, or any of us, received from Joe. He was a great man who set aside his own work to preserve the legacy of another great man. Joe in his humility and wisdom truly lived from a spiritual center.”

***

Maciariello is survived by his wife Judy; two sons, Patrick Anthony (Aleeza) of Laguna Hills, and Joseph Charles (Lauren) of Mill Valley; a brother, Lawrence; five wonderful grandchildren, Callie, Reese, Grace, Alice, and Charlie; as well as many brilliant nieces and nephews.

- Read more about Joseph Maciariello’s life here.