Michael Shermer and the Science of Morality

The CGU adjunct professor says science–not religion–should decide right from wrong

There are no bad questions; only bad ideas.

When we talk about the difference between a wrong idea and a bad idea we are talking about the difference between holding an incorrect—-albeit harmless-—viewpoint and having an incorrect viewpoint with harmful consequences. Don’t believe in black holes or string theory? No big deal. Believe that vaccinations cause autism? That’s a bad idea, since it leads to parents not vaccinating their children, causes a delay in the study of autism, and causes a breach in herd immunity. A very bad idea, indeed.

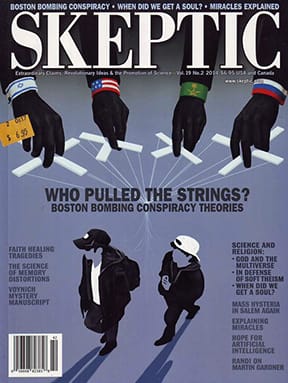

That’s the argument CGU alumnus and adjunct Professor Michael Shermer (PhD, History, 1991) makes. Shermer, the founding editor of Skeptic Magazine and executive director of the Skeptics Society, has made a mission out of promoting proof-based critical thinking, in addition to debunking fringe science like ESP and other paranormal claims.

For Shermer’s next project, he aims to expose what he says is one of the most prevalent bad ideas of our time: that the fountainhead of humanity’s moral compass lies in the Bible.

The concept of morality has vexed philosophers, theologians, and politicians since time immemorial. Do laws dictate moral behavior? Is there an innate human sense of right and wrong? Do we need to rely on holy texts to provide us with a template for morality?

“The idea that the Bible is the source for morality is not just wrong, but a bad idea,” said Shermer, who has taught in CGU’s Transdisciplinary Studies Program since 2008. “First, people don’t actually get their morals from the Bible, and that’s a good thing! Because if you follow the Old Testament mentality then forget it: slavery, death penalties for adultery, and stealing: it’s not a moral code anyone in the West would follow today. Elsewhere in the world, we can see the implications of this Bronze Age moral system in fundamentalist Islamic countries that follow Sharia law. The New Testament is a little better, Jesus is more liberal, more of a feminist, more egalitarian, but still, if you read what he said, you wouldn’t follow most of that, either: ‘I come not to bring peace but I come to bring a sword.’ And should we really ‘turn the other cheek’ if a criminal breaks into our home, or if a Bernie Madoff con artist steals our money? I don’t think so.”

For Shermer, morality can be determined via science and reason.

When we think of science, we tend to picture it in action: test tubes, experimentation, and the like. But, Shermer says, when we regard science as the basis for moral behavior, we are referring to the scientific method, using the tools of science—reason, empiricism, and testing hypotheses—to analyze claims. With intellectual roots in the Enlightenment—the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century movement that focused on the primacy of individual reason versus tradition—reason and scientific thinking has given humanity some of its best, and most progressive, ideas yet, he contends.

Shermer is no stranger to investigating—and challenging—beliefs.

In 2012, Shermer, along with CGU economics Professor Paul Zak, was named to the 2012 Wellcome Trust Book Prize longlist, which recognizes fiction and nonfiction books related to health, illness, and medicine. The prize was awarded for Shermer’s The Believing Brain, which centers on how beliefs are born, formed, nourished, reinforced, challenged, and extinguished.

In his prior writings, he has criticized ideas such as Holocaust denial, intelligent design, and JFK conspiracy theories. In one noteworthy case, Shermer was skeptical regarding global warming but changed his mind after a “convergence of evidence” convinced him in 2008.

Science and reason should be the benchmarks by which beliefs and ideas are measured, according to Shermer.

“John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson, what these guys were looking for—what scientists do—were natural causes and explanations,” said Shermer, who was also a senior research fellow at CGU’s Center for Neuroeconomic Studies from 2008 to 2011. “And they believed—as we do today—that natural causes can explain everything from planets and solar systems to economies and political systems. It was all understandable through reason and empiricism. Everything we do, liberal democracies and free-market economics, and all these things that seemingly have nothing to do with science and reason are all grounded in the Enlightenment’s effort to create a rational world.”

Shermer’s upcoming book, The Moral Arc: How Science and Reason Lead Humanity Towards Truth, Justice, and Freedom (inspired by the famous quote by Martin Luther King Jr., “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice,”) shows how, historically, most of the ideas we have today about moral values, civil liberties, civil rights, women’s rights, and gay rights, are borne not from sacred texts but from the application of reason. Shermer makes the point that religion can’t provide the same kind of moral roadmap. Religion does not require proof and is mired in a self-sustaining loop of confirmation biases and ideology.

“In religion, there is no mechanism to determine what is right about the world. It’s just ‘I’m from India so I’m Hindu,’” said Shermer, also a monthly columnist for Scientific American. “If you went to India and discovered there was, say, a different type of physics, you would be, like, ‘whoa, what is going on here?’ because there is only one physics. That is the way the world is, and that’s it.” In other words, the plurality of ‘right’ religions, philosophically, negates the possibility that anyone could be right. But science and reason transcend faith and geography and offer evidence-based answers untainted by ideology and faith.

But questioning, using reason and critical thinking, and putting ideas to the test does not mean one cannot also be religious.

“Skepticism is just a way of asking questions about the world and answering them using scientific reason,” Shermer said. “So to the extent that you use reason and science it doesn’t matter if you’re politically left or right or what your religion is, because skepticism isn’t a thing or a position you stake out, it’s just a methodology.”

Shermer’s The Moral Arc is being published by Macmillan and will be available January 2015.

To see Shermer discussing skepticism and critical thinking, click on the video below: