PhD student David Okonyan Studies Genocide—and Denial

Acknowledging the Unacknowledged

PhD history student David Okonyan studies the largely unrecorded Armenian Genocide

On November 9, 1938, Jewish homes, businesses, and synagogues across Nazi Germany were destroyed, and nearly 100 Jews were killed while 30,000 more were sent to concentration camps. Known as Kristallnacht (“the night of the broken glass,” a reference to the shards of glass left from the broken windows of Jewish businesses), this atrocity is remembered as the first act of the Holocaust, the slaughter of an estimated six million Jews and five million others.

Today Jews and non-Jews around the world remember these atrocities on Yom HaShoah.

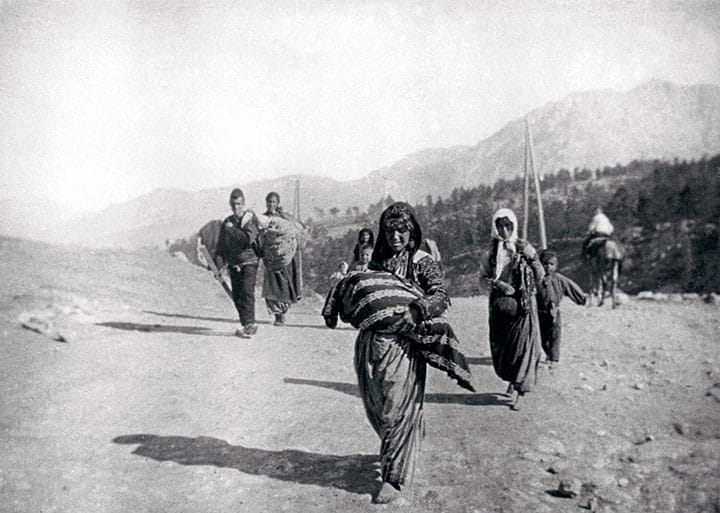

Nearly a quarter-century before Kristallnacht, Turkish officials in the Ottoman Empire arrested and executed some 200 Armenian leaders in Istanbul. These killings on April 24, 1915, became known as Medz Yeghern (“Great Crime”), the event that signaled the start of the Armenian Genocide; the slaughter of an estimated 1.5 million Armenians.

Although the Holocaust and its day of commemoration are universally recognized, such has not been the case for the Armenian Genocide. Today, more than 100 years after the start of the Armenian Genocide, scholars, activists, and governments are still asking, why has it taken so long?

David Okonyan is seeking to answer that question.

A PhD student (MA, History, 2011) in history, Okonyan is examining the forces that have shaped how the deaths of 1.5 million Armenians are recognized and interpreted. His dissertation will look at how Armenians have tried to study and memorialize this event and unravel the challenges faced in creating a scholarly record in the face of those—such as the Turkish government—who fiercely dispute that the event should even be considered genocide.

“Practically Unheard Of”

One of the earliest challenges to the Armenian Genocide is based on a linguistic reason: During the decades following the 1915 killings, there was no word to describe the systematic killing of an entire ethnic group. The term genocide would not be coined for nearly 30 years.

“When the Armenian genocide unfolds, people are looking at it saying they’ve never seen this before,” said Okonyan, who also teaches history at Chaffey College. “At the time, there was no term ‘genocide’ and it was practically unheard of for a government, state, or empire to kill its own population.”

It was not until Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin published his 1944 book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe that the term “genocide” was coined to describe the “destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group . . . [marked by] a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves.”

The United Nations didn’t create laws and legal sanctions around genocide until 1948, which allowed the perpetrators of the Holocaust to be charged with crimes against humanity.

In fact, as Okonyan has learned in the course of his research, the legal framework for classifying and punishing those responsible for mass, ethnic killings was so nebulous before 1948 that when the Nazis gained power in Germany, they took heart in the lack of accountability that the Turks had faced over the Armenian killings. Famously, on the day of the invasion of Poland in 1939, Hitler ordered his troops to be ruthless and kill as many Poles as possible, suggesting they would not be held accountable for their acts, saying, “Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?”

“But this is where the issue [of accountability] gets really complicated,” said Okonyan. “If we call what happened in Armenia a ‘genocide,’ Turkey has to pay [reparations] for that crime. So Turkey goes out of its way to call it a ‘civil war’ with the Armenians or a ‘massacre’ perpetrated by both Armenians and Muslims. There are all these denialist efforts that Turkey has gone to over the past 100 years to combat having to make reparations.”

But the denial is also rooted in decades-long geo-politics.

A Very Important Relationship

“Strategically, Turkey becomes very important [to the United States] after the Russian Revolution; it is a Middle Eastern democracy that is an ally to the West against communist Russia,” Okonyan explained. “During the Cold War, the United States had military bases in Turkey that we still use, whether in the war with Afghanistan or the war with Iraq. Turkey is one of the only Muslim-majority countries in the Middle East that has a democracy, a very important relationship for the United States to maintain.”

Considering the European Union has said that Turkey can be considered for membership without requiring its recognition of the 1915 atrocities, the chances for acknowledgment and reparations appear slimmer than ever.

But that doesn’t mean that scholars, activists, and certain governments have given up trying. Argentina, Belgium, Canada, France, Italy, Russia, and Uruguay are among the 20 countries that have formally recognized the Armenian Genocide.

Okonyan’s dissertation will look at how Armenians have attempted to study and memorialize this event and how to create a scholarly record for what happened without the corroboration of the perpetrators.

“Before It’s Too Late”

Those who study the Armenian Genocide encounter advantages—and drawbacks—different than those faced by Holocaust scholars.

“One advantage that Holocaust scholars have is that the German state does not deny what happened, and they accommodate requests for records. And there are a lot of records in terms of letters, photographs, etc.,” Okonyan said.

Fortunately, his project looks at the work of Armenian documentarian Michael Hagopian, who, along with directing over 50 documentaries about ethnic minorities in foreign lands, has filmed around 400 interviews with Armenian Genocide survivors from the 1960s until his death in 2010.

“I see in Hagopian’s work a complete reappraisal of how an archive can function,” Okonyan said. “He’s not relying on validations from the perpetrators of a crime to bring it to light: he’s focusing on the survivors.”

Hagopian’s work, Okonyan explained, has resulted in two effects.

“In this way, Hagopian’s work has a dual function: to create awareness in society at large and to create an archive for future scholars, all without the corroboration of the Turks,” he continued. “In other words, the adage that ‘every story has two sides’ isn’t important to Hagopian: It’s about telling the story now, from the side of the remaining survivors, before it’s too late.”

Politicized Issue

“David’s work is important in examining some usually overlooked components of the Armenian Genocide,” said Joshua Goode, chair of the department of history and associate professor of history and cultural studies.

Goode emphasized that Okonyan’s work provides a fresh understanding of the how along with the what.

“While historians have examined so many facets of the bloody crimes of the twentieth century, only in the past few decades have we begun to examine not just what happened but how we remember and commemorate these events, that in the act of memorializing there is a politics,” he explained. “David is examining an important facet of this process; how [more than] one hundred years of denial have affected not just what we remember, but how we remember it.”

On April 24, 2015, the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation released a large portion of Hagopian’s films online, creating a publicly accessible visual record. Filmmaker Steven Spielberg—who directed and co-produced Schindler’s List—established the foundation in 1994 to make audio-visual interviews with survivors and witnesses of the Holocaust and other genocides freely available.

That same day, Armenians in Los Angeles made their annual march from the Little Armenia neighborhood in Hollywood to the front steps of the Turkish consulate to make a case for recognition. Armenians living in Los Angeles comprise one of the largest communities of the Armenian diaspora.

“Although this is an immensely politicized issue, recognition and study of the Armenian Genocide is intrinsically important,” Okonyan said. “For Armenians, it is the event that has over-determined so much of their history.”

And not just Armenian history—it also set the tone for the century ahead.

“For humanity, this pivotal event was the dawn of the ‘Dark 20th century,’ in which genocides, world wars, nuclear weapons, and mass atrocities cast a shadow on the ideals of the Enlightenment and brought us into the post-modern world,” he explained. “Without understanding why this event quickly faded into the dustbin of history, we deprive ourselves an opportunity to understand one of the defining moments in world history.”