Crano talks drug prevention strategies in a country ravaged by opioids

With the growing use of fentanyl and other powerful (and lethal) opioids, Brazil’s drug problems are getting worse. In addition, with Brazil’s neighbor, Uruguay, having legalized marijuana, Brazilians are focusing on prevention to try to offset the problems that their neighbors might create for them.

Health professionals there are on edge as the number of deaths from overdoses continues to rise—especially among young users tempted by the intense highs promised with such a deadly combination as heroin laced with fentanyl. Use of other psychoactive substances also is worrying. Meth and marijuana seem particularly popular among Brazilian youth.

- Read more about Brazil’s rising problem with drug overdoses here.

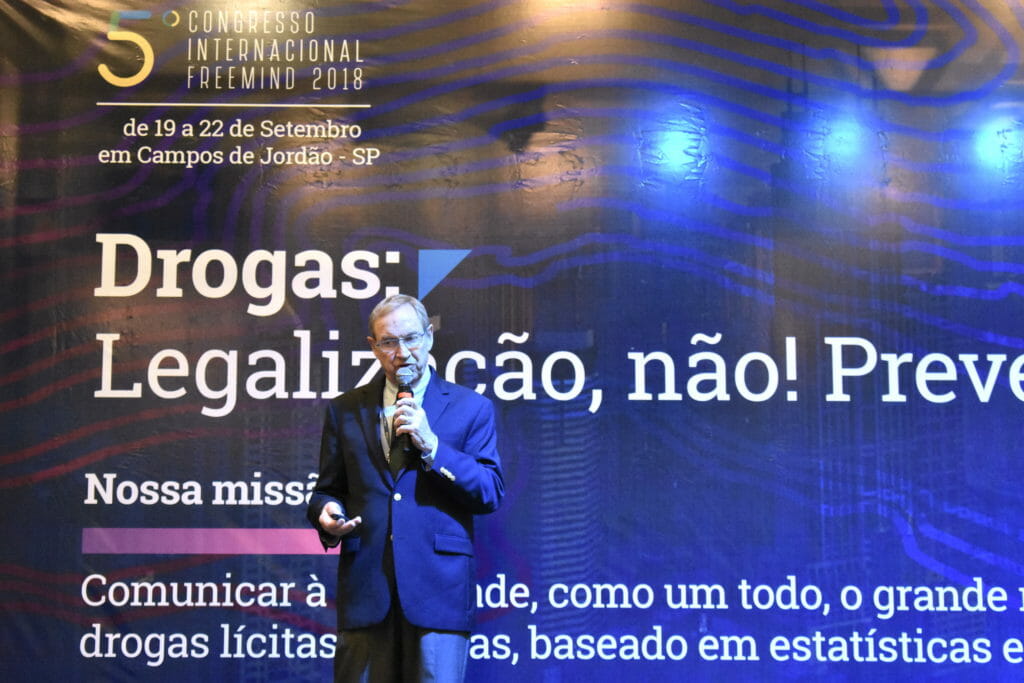

DBOS’ William Crano traveled to Brazil this fall to address the substance use crisis in his keynote remarks at the international conference, Espirito Freemind. Crano addressed an audience of some 1,400 substance abuse prevention and treatment professionals.

He also led a training course on the Universal Prevention Curriculum for Media-Based Prevention that he developed for the State Department and the Colombo Plan, to Brazilian professionals.

“They’re having a big problem there. It could be even worse than ours,” said Crano, a leading figure in the field of international drug prevention efforts and the holder of the university’s Oskamp Chair in Psychology. “Nobody knows what to do. Prevention models often are not based on evidence. They’re handled in a by-the-seat-of-the-pants way, and as a consequence, they usually fail. It’s not evidence-based, and that’s what it needs to be.”

To drive the point home that prevention must be evidence-based, Crano’s keynote—titled “Exporting Laboratory Science to Mass Media Persuasion Campaigns”—addressed the need for better uses of the research and evidence we have on how to persuade people when developing media-based messages to alert them to the dangers of substance use and addiction, especially among the adolescent population.

“Adolescents are taking huge chances and they have no idea what they’re doing,” he said. “That’s what really motivates me—to get to these kids. And if that’s going to happen, if we are going to succeed, the media has to use better persuasive techniques to reach them.”

Prevention Instead of Recovery

Conference organizers invited Crano as a result of his extensive involvement with the drug prevention efforts of the United Nations and U.S. State Department.

Crano said one of the biggest problems that prevention proponents face—especially when it comes to getting funding—has to do with the fact that funders often overlook prevention and focus immediately on treatment and recovery efforts. “These efforts are clearly necessary, but we believe prevention is the best treatment.”

“They’re thinking that the goal is to get users clean and keep them straight,” he said. “But it’s even more important to stop them from ever starting. That’s where we need to focus our prevention efforts.”

He’s also very candid about the mistaken assumptions some people bring into the field of prevention.

“I tell them that if you’re going to do this kind of work, you can’t assume that you’re smarter than everyone else and that you’re going to find the magic formula. “It’s been tried a thousand times before, and it has failed. You have to develop prevention messages that are based on the science of persuasion,”

He emphasizes the importance of the appropriate use of strong media messages and involving parents, whose role as opinion leaders can make all the difference.

“Some parents don’t want to be involved because they think they don’t know enough and don’t want to be embarrassed in front of their kids,” he said. “But I tell them to forget that. All they need to say to their kids is something like, ‘Look, if you take something that alters your perception, it might do something to your brain. Do you really want to take that risk?’ When parents do even just that, it’s been shown to have a strong effect.”