A Portrait of the Artist as a Soldier and Survivor

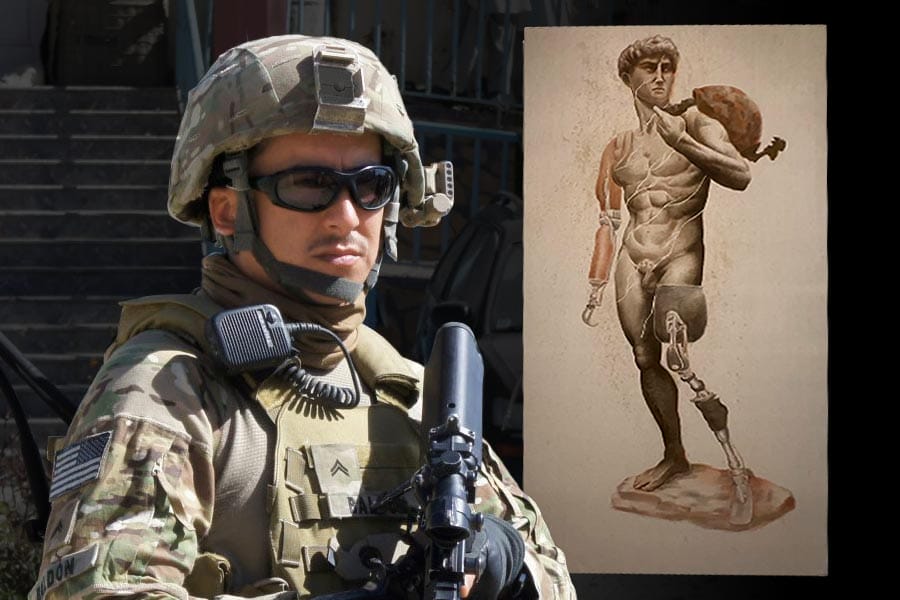

The image is familiar but haunting: Michelangelo’s David stares into the distance, but instead of clutching a sling pouch, he is holding a soldier’s helmet. His right arm is missing, as is his left leg below the knee. In their place: prosthetic limbs.

The Returned Warrior takes the idealized male form and mutilates it, much like what can happen to those in combat. The striking artwork, painted in high-flow acrylic on raw linen, is the creation of Aaron D. Baldón, the 2024 President’s Art Award recipient.

War and its horrific effects are not abstract concepts for Baldón. They are seared into his psyche from his time in Afghanistan and, later, Ukraine. Other works in his collection include Loading Ammo, Then This; Defeated; The Last Thing You See—Internal Scream; and The Aftermath of War.

“I don’t try to create palatable images, because the world can be a dark and brutal place, and I’ve been there,” Baldón says. “I take some inspiration from Goya in that he worked in a journalistic fashion. While he can say, ‘I saw it,’ as can contemporary journalists, only a soldier or anyone else caught up in a war can say, ‘I felt it.’”

To understand the artist, you need to know his roots.

Baldón grew up in an economically disadvantaged but culturally rich Chicano community near downtown Los Angeles, the child of a Mexican American mother and an Indigenous father from a pueblo in New Mexico. His grandmother, who came from a small village in northern Oahu, was another major influence.

The neighborhood inspired his aesthetic and artistic style. Striking, stylized murals cover walls and buildings, and tattoo artists practice their craft in shops and salons.

Baldón took his passion into the professional world as a freelance art director for companies such as Mattel, overseeing high-profile projects and managing teams of photographers, illustrators, and designers, but over time he grew disillusioned with the work. The turning point came on a trip from L.A. to Louisville, Kentucky to sign off on a project for a major client.

“I got off the plane and there was a black car waiting for me. Meanwhile, on the same flight, was an exhausted, young soldier on his way back to his unit in Kentucky. This stood out in stark contrast to me. I have black car service the whole time that I’m there because I’m the art director. I’m basically there to make sure it’s the right shade of green, and then I go back to my hotel. On the flight back I thought, ‘What am I really doing with my life when there are others willing to sacrifice so much?’”

In 2010, at age 36, Baldón joined the Army.

Basic training was at Fort Knox, south of Louisville, an irony not lost on him. “I was back in the same place, but instead of a black car, I was on a bus with all the other recruits—and we got yelled at as soon as we got off that bus.”

After advanced training at the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School in North Carolina and qualification as a civil affairs specialist, Baldón was deployed to a mountainous region of Afghanistan to meet with tribal and government officials, work with the local population, and coordinate humanitarian missions. His duties also included providing security and operating heavy weapons.

“I became deeply and emotionally entrenched in the experience of a soldier and war’s impact on the surrounding population,” he says. “It’s an almost indescribable juxtaposition of beauty and danger.”

After six years, Baldón left the Army, earned his bachelor’s degree in art at the University of La Verne, applied to CGU, and headed to Ukraine in 2019 to teach English for a year.

Why Ukraine?

“I wanted to go somewhere cold because I grew up here in California and I was just tired of the hot weather. I considered several places where I was either looking at jobs or got offered jobs and I put them into a spreadsheet—the Army decision matrix—and Ukraine scored the highest, much to my surprise.”

The matrix decision changed his life in profound ways: He met his future wife two weeks later in a café after hearing her practicing English in a group next to him. He intended to stay just a year, but he signed a second teaching contract when COVID hit. He began his MFA studies at CGU online, with classes usually taking place around midnight in Kyiv.

Though Baldón had planned to return to the US to continue the final year of his master’s program in early 2022 (with his fiancé and her son set to join him at the end of the year after his graduation), he instead began stocking up on food, water, and other necessities because he could see that war was on the horizon.

They were in their apartment north of Kyiv on February 24 when Russian forces invaded, partially encircling the area and firing on civilian vehicles that tried to escape. After a month of enduring the battle near their neighborhood, they managed to flee to a farming village in Croatia, where they lived as refugees for a year and married.

“This experience gave me yet another perspective on war,” Baldón says. “I saw its effects on people very close to me who were not soldiers. War scars everyone, whether physically or emotionally. It reshapes landscapes—physically, culturally, and ethnographically.”

In March 2023, Baldón returned with his family to Southern California. He resumed his education that fall at CGU, where he thrived in the MFA program. He graduated this May, a day after being honored with the Art Award at a dinner hosted by CGU President Len Jessup. The award includes a $5,000 honorarium and the distinction of having The Returned Warrior join the university’s Presidential Art Collection.

“Despite the ugliness of conflict and the darker aspects of the world, I aim to combine it with the elegance of mastery of my craft,” Baldón says. “I want to use art as a tool to invite reflection, understanding, and empathy.”

He hopes to teach at a university and, inspired by his father’s experiences, he wants to mentor aspiring artists in economically disadvantaged areas. He also wants to show his work in galleries to raise awareness about the harsh realities of war.

“It’s glamorized and sanitized, but there’s nothing glamorous about it.”

Baldón makes it clear, however, that he values his experience in the Army and admires those who serve their country.

“From a paraphrased quote attributed to George Orwell, people sleep peacefully in their beds at night only because rough people stand ready to do violence on their behalf.”