Cultural Studies Alumnus Ian Fowles and his Rock n’ Religion Theory

Stairway to Heaven

Religion PhD student and cultural studies alumnus Ian Fowles has toured the world and met the faithful. He’s seen the devoted sob for their idols. He’s heard them sing their holy verses. And he’s witnessed as they worshipped at their shrines.

But these believers aren’t following the teachings of Jesus, Buddha, or Muhammad. Rather, they’re more likely disciples of Elvis Presley, John Lennon, or Bono.

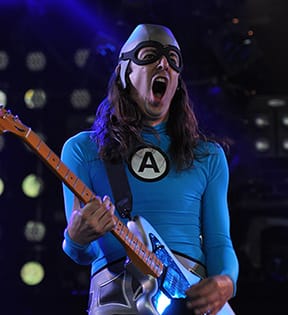

Fowles, lead guitarist for the popular Southern California rock band The Aquabats!, combines his passion for music with his studies at CGU to propose a novel theory: rock and roll is a legitimate religion.

“It fulfills all the criteria that anybody needs to qualify for an academic study as a bona fide religion,” he said. “It has its deities, its own rituals, and its own scriptures. And there are millions of people who have rejected institutionalized religion or whatnot who have their spiritual void filled by music.”

Fowles’ theory coalesced while he pursued his master’s degree at CGU, and he published it as his thesis. He has since turned it into a book, A Sound Salvation: Rock N’ Roll as a Religion, which features an image of a saint-like Jimi Hendrix on the cover.

He does not suggest that listening to a CD in your car or singing along at a concert makes you an adherent to the faith. Rather, as America’s faith in traditional religious institutions dwindles, rock and roll is filling certain religious needs for millions of the nation’s lost souls, whether they are consciously aware of it or not.

As Fowles explains, rock’s biggest stars become its deities, the heroes who are larger than life and the subject of mythology and worship. No example better illustrates this than the King of Rock, Elvis.

“You have a humble birth, and people said there was a blue light in the sky when he was born,” Fowles said. “When he grew older, he did good deeds like giving people Cadillacs. He surrounded himself with the ‘Memphis Mafia,’ which is kind of like a body of 12 disciples. And he died in a mysterious way; some people claim he’s not really dead.”

The scripture, meanwhile, is the music. Some musicians foster this comparison with claims of songs coming to them in a sort of divine intervention (Keith Richards said he practically wrote “[I Can’t Get No] Satisfaction” in his sleep; Paul McCartney composed “Yesterday” in a dream), which makes the creative process a sacred experience, Fowles said.

“And the most devoted fans memorize these lyrics and use them to guide their lives like teachings,” he said. “Sometimes they tattoo them on their bodies. It can be a touchstone or reference point for everything they do, as if it were scriptures in the Bible or the Koran or the voice of a prophet or a god.”

And then there are rock and roll’s holy places. Shrines like Elvis Presley’s Graceland in Memphis, or the gravesite of the Doors’ lead singer Jim Morrison in Paris, where fans flock to pay tribute with gifts and offerings.

The holiest of these are the concert venues themselves, which, like churches, are the soil from which springs the rawest ritualistic behavior of the faithful. Once a fan crosses the threshold and enters the space, there’s an unwritten code, Fowles said.

“You watch the way some people react to musicians on stage. They’re worshipping them,” he said. “They’re screaming and shouting the lyrics. People are dancing, doing the circle pit if they’re into punk rock, or moshing, stuff like that. And when they leave, they’re refreshed and renewed as a person.”

Richard Bushman, the former Howard W. Hunter Chair of Mormon Studies in CGU’s religion program, was a professor of Fowles. He said researchers have seen religious dimensions in all sorts of nontraditional institutions, from the stock market to shopping malls. In that sense, Fowles is pursuing a familiar and legitimate inquiry in modern religion studies.

However, Fowles’ work on rock and roll is cutting edge in that he is recognizing aspects of this music that have not been noticed before, Bushman said.

“As a religious person himself, he reacts to how the music affects people in ways a more secular listener might not recognize,” Bushman said. “Religion is becoming increasingly interesting to historians, sociologists, and anthropologists. Where we once thought secularization was steadily erasing religious impulses from modern life, scholars now see those basic human urges reassert themselves in new locales. Ian is advancing that line of inquiry.”

Fowles’ firsthand experience with rock stardom laid the foundations for his theory and research.

Raised a Mormon in Southern California, he joined his first band by age 14. Less than three years later, while still in high school, he had already played shows in the legendary clubs on Hollywood’s Sunset Strip. He joined his most successful band, The Aquabats!, in 2006.

The Aquabats! aren’t a typical rock band. The five-man group has adopted the playful personas of crime-fighting vigilantes. Members take on cartoonish alter egos and wear rubber helmets, masks, and matching costumes when they perform.

Fowles plays the character of Eagle “Bones” Falconhawk, a nod to his avian surname and his thin, birdlike stature. His character shoots a laser from his guitar and summons an invisible bird to help him battle bad guys.

Fowles and The Aquabats! have parlayed their superhero act not only into a successful rock career, but also a popular children’s television show. The Aquabats! Super Show!, which just completed its second season on the Hub Network and is available on Netflix, was nominated for a 2013 Daytime Emmy Award for “Outstanding Children’s Series.” The show is smart, musical, and funny, borrowing from campy 1960s kids’ programs like Batman and The Monkees.

With this crossover success, the band has developed a broad, cult-like following. Fans, who call themselves Aquacadets, turn out for concerts in the costumes of their favorite Aquabat.

Before the band performed at the Vans Warped Tour at the Fairplex in Pomona in June, the most dedicated Aquacadets waited in line for up to an hour for autographs from Fowles and his bandmates. But it wasn’t until the band took the stage that their broad appeal became most evident.

Four-year-olds, 40-year-olds, and teenagers danced and sang as the band jammed through its biggest hits. Keeping with their superhero personas, the Aquabats battled a hulking, villainous wolf that lumbered onto the stage midway through the show. And the crowd rejoiced.

Though his routine with The Aquabats! is playful, Fowles takes his academics quite seriously.

He earned his master’s degree in 2008 and has completed his PhD coursework in History of Christianity and Religions of North America.

Coming from a Mormon background, Fowles struggles with the question of how his theory squares with his own religious beliefs, saying he has done his best to maintain scholarly objectivity. Yet he has met fans who traveled thousands of miles to see him play. Some have tattoos of band logos and artwork, tributes he describes as “flattering and yet also very intense.” It’s possible that some of these fans feel a spiritual connection to his music, but that’s not what motivates him, he said.

“As a musician, or any type of artist that is creating something and putting it out into the world, we have very little control over how that work will be received, interpreted, and manipulated,” he said. “Will it create fans? Will it create stalkers? Will it create a cult? Will it change a life? I don’t know how much conscious thought many songwriters and artists put into the potential religious-type effects a song will elicit from an audience. A lot of times they just a have a song or a poem or an image or whatever that they need to get out of them, something that’s burning inside. They just want to make the best music they can, and if people like it, then that is an added bonus.”

Though he continues to build on his theory, his dissertation is on hold while The Aquabats! develop their television show. They’ve filmed 18 episodes so far, and are preparing scripts and negotiating for a third season.

The band also stays busy touring. It recently returned from Europe and spent the summer playing West Coast dates of the popular Vans Warped Tour.

“With the entertainment industry, you have to strike while the iron is hot,” he said. “Not many people get a chance to have their own TV show, and I’m not even a trained actor, so I can’t pass up this opportunity.”

When he eventually steps away from his work as an entertainer, Fowles intends to finish his PhD and hopes to teach, ideally in either religion or rock and roll history (though, if his theory gains wider acceptance, those might become the same thing).

He credits CGU for being open-minded and giving him the freedom to blend his love for music and his passion for the study of religion into a singular field of study.

“CGU is an ideal place to do this kind of work,” he said. “It’s in the perfect location, a half-hour from Los Angeles, where you have the heart of the music and film industries. The professors are really open-minded about what you can study, and they’ve been really cool about letting me pursue these avenues.”

Learn more about the Mormon Studies program at CGU:

Loading...